Core Surgical Training (CST) is the gateway to higher speciatly training to many surgical specialties. It is both popular and competitive. In this article, DR M K discusses his approach to preparation, resources he found most helpful, and tips to do well in both the MSRA and then the interview. Dr M K ranked near the top of the defence deanery rankings (initials used as Dr M K is a military doctor in active service).

Part 1 – How to Prepare for the MSRA

The Multi-Specialty Recruitment Assessment (MSRA) is the gatekeeper for Core Surgical Training applications. You must score above the cut-off in order to secure an interview. The cut-off will vary according to applicant numbers. On recent trends, we can expect upwards of 5 applicants per spot, so a score well into the top quarter will reasonably be required to rank for interview. Being able to work to time and apply exam technique is half the battle in this exam! We are all qualified doctors who have succeeded at rigorous exams regularly throughout our adult life and adolescence. The word revision has likely made you gag over the years, but this article should help to catalyse your preparation for best chance of success.

The MSRA is worth 10% of your overall score in Core Surgical Training applications, with 90% falling on the interview, part of which covers your portfolio. The interview and how to prepare for it is covered in more detail in the second half of this article.

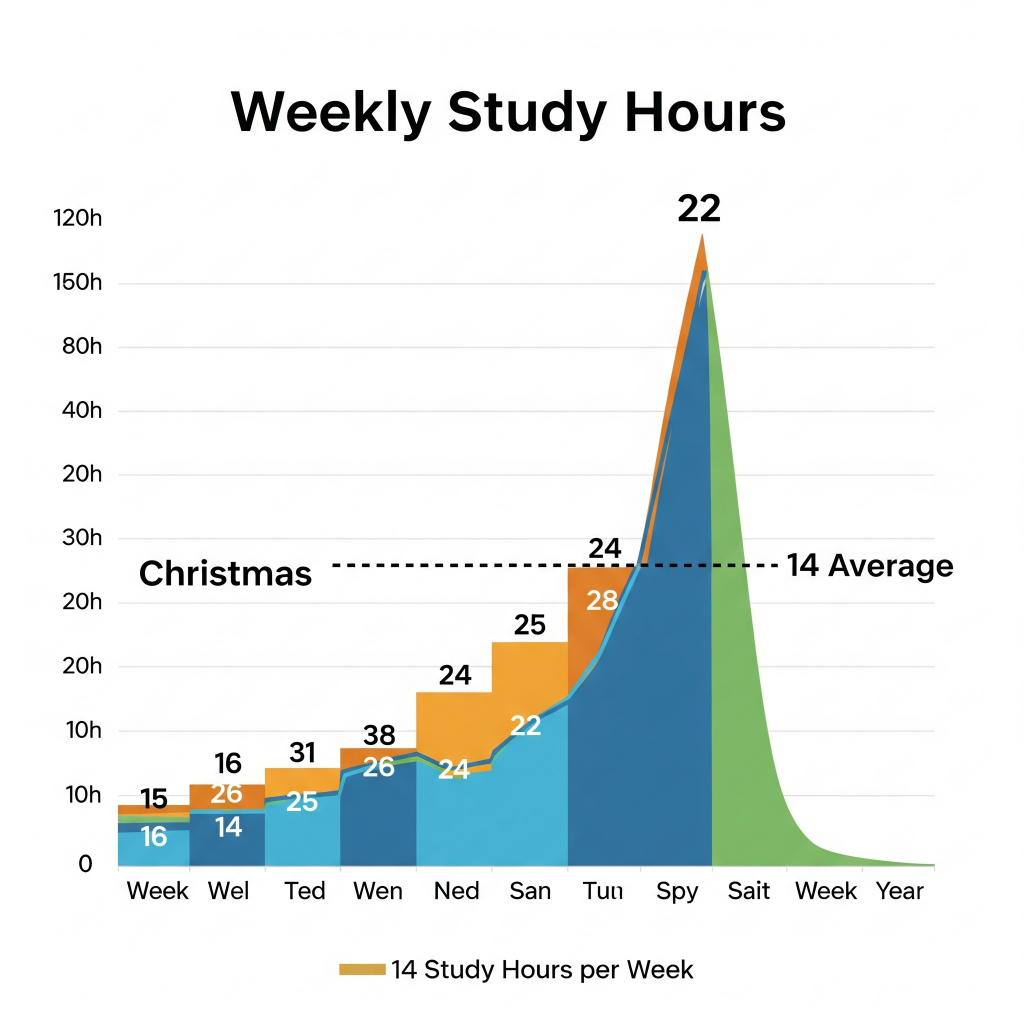

Back to the MSRA: as you can see from my preparation timeline above good preparation for this examination will take a good chunk of time. I spaced my 200 hours of prep out over 3 months at an average of 14 hours a week, but realistically the workload peaked over the Christmas and New Year period. Over this period, I had two weeks of annual leave, followed by a week of study leave. This was a blessing and a curse, as it allowed my full attention to be on revision, but also meant I burned out around New Year and had to take a break. In my experience, diminishing returns came from around the 100-hour mark – but I had the spare time so could press on.

A critical first step is to shaping activity to understand the examination you are sitting. I read official and unofficial websites on the structure and content of the examination and then leaned in to colleagues from last year’s candidates to learn from their experiences. By discussing revision strategies with those in the same specific role I was able to structure my preparation around the job. It also protected me from revision pitfalls and misdirected preparation. We each have varying levels of life complexity with care responsibilities, children, commuting, shift patterns, our own disability. I would encourage establishing fixed blocks for revision across the week such that it is easier to plan cover and support, and in this sense manage your cognitive load. Absolutely engage with Educational Supervisors and bosses to free up study leave. If you have reason to seek extra-time then ensure you do so early as soon as invited to apply for MSRA.

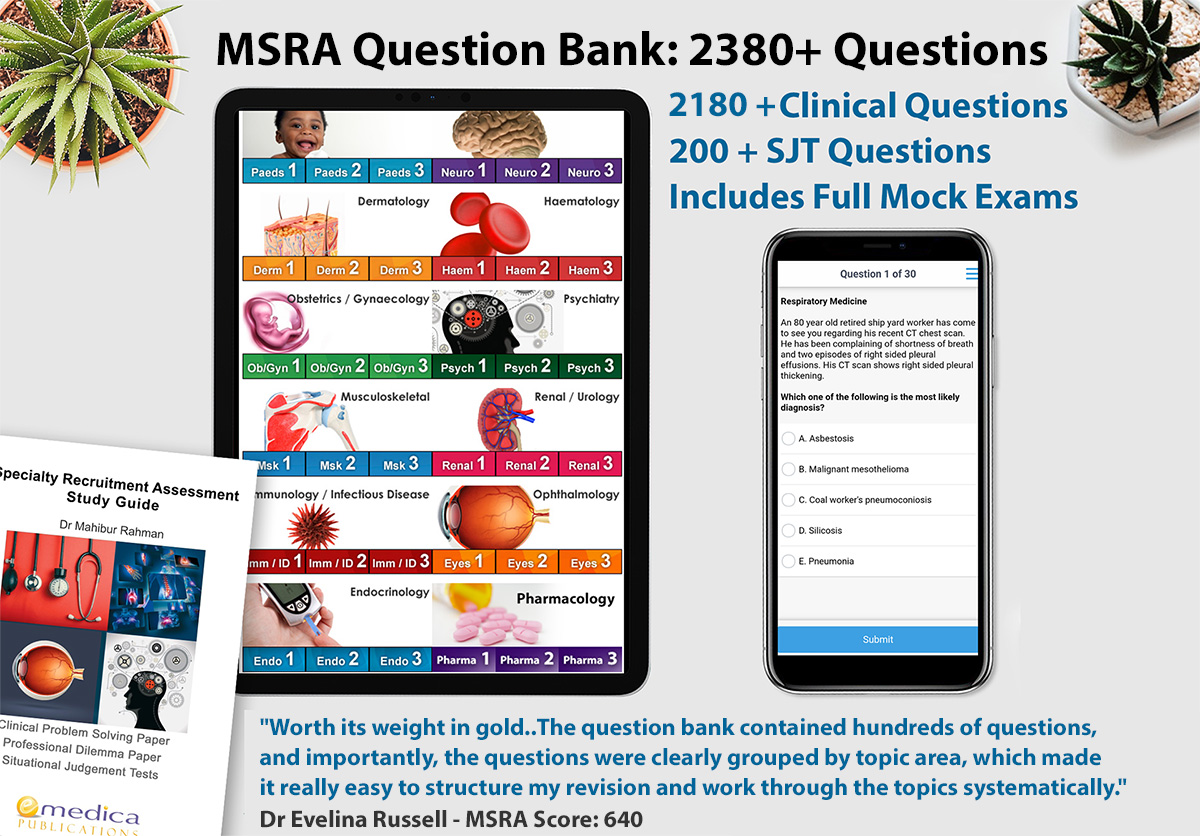

Following on from this I surveyed the market for MSRA preparation resources, including those recommended by colleagues. Most advised a dual question bank approach to ensure volume was achieved, as while maintaining adaptability. Emedica came up again and again as the question bank most closely resembling the MSRA. Additionally, it demonstrated a building blocks approach, with comprehensive question banks on each subspecialty, building into half and full-length mock examinations, including situational judgement questions – which many banks did not have.

Of my own volition I came upon Medibuddy adaptive question bank and opted for this as a secondary, due to it’s 4000 questions and adaptive algorithm. It complemented Emedica nicely and ensure I never ran out of freshly presented questions – despite medicine’s vastness, you will soon discover there are only so many questions that can reasonably be asked. For both of these question banks I was able to access my study budget.

My personal revision strategy can be summarised into general revision, gap analysis, targeted revision and then cycling mock exams and further targeted revision.

Gap analysis

The shaping activity of understanding MSRA’s content and form is essential to setting the desired end state. Our start state is likely to be a somewhat rusty medical knowledge, having sat finals at least 2 years previously! Using records of my finals revision, I was able to appraise how much time would be required and added an extra 20% on top to account for the added complexity given the FY2 experience level assumed by MSRA. Buried memories will still exist on the niche medical knowledge, so be sure to regularly conduct gap analysis throughout the course of your revision to ensure you understand the revision required and can plan adaptively.

General revision

I began by reading over the Oxford Handbooks of Clinical Medicine and Clinical Specialties to jog my memory – passive revision I know. But I always find this helps to get me into the mood when a revision season is coming on. It is also verified information and concise so is on the high value proposition for passive revision. I spent approximately 20 hours on this right at the start of my revision block.

Question banking and targeted revision

Whilst reviewing Oxford handbooks I made note of my weak areas – volume sections such as nephrological conditions to common treatment pathways. There is just some information that is abstract and will have to be learnt rote. I like to write things out on a page Bart Simpsons style or generate mnemonics to imprint into my brain.

I began question banking specialty by specialty on Medibuddy. After answering each question, the correct answer is provided alongside an explanation and reference. Its adaptive algorithm ensures that you cycle through incorrectly answered questions in ratio to new questions and previously correct questions. This reinforces content, without changing tack to often. My approximation was that the ratio was 50% previously correct, 25% previously incorrect and, 25% new – although sometimes 50/50 if I was struggling on the same questions. Of course, you can adapt this in settings to only offer new questions or only offer incorrect questions. I find I best maintain motivation by having questions I do know the answer to thrown in there. It makes the process slightly longer, but I trust in the algorithm. The Medibuddy dashboard displays percentage completion for each specialty. I chose to work through each specialty one by one, getting to 80% plus before progressing to the next. I occasionally threw in an all-cards session to practice changing tack between specialties. Typically, I worked in blocks of 1hour on 15 mins off. But the benefit of Medibuddy is its app, which allowed me to snatch revision from previously ‘dead’ time.

Half mock exams and targeted revision

Emedica breaks down each specialty into 3 modules of increasing complexity. Once I had exhausted Medibuddy I switched to Emedica in order to take in another angle. Emedica is excellent in providing concise explanations for each question. There are also exam technique explanations and information pages. Emedica’s questions were high quality, although fewer than Medibuddy’s cover all bases approach, where sometimes the question quality was lacking.

I interspersed Emedica’s half mock examinations with targeted revision based on the previous paper’s weak spots. Some people use mock examinations as confirmatory exercises. I find it more useful to use mock examinations to motivate myself but also to reward myself. It is motivating to see a lower score; it is also motivating to see a high score. Being able to work to time and apply exam technique is half the battle in this exam! We are all qualified doctors who have succeeded at rigorous exams regularly throughout our adult life and adolescence. Do not sell yourself short by not understanding the exam situation and how you need to use the information provided.

Full mock examinations

I graduated to the full mock examinations later and set myself a fixed amount of time per question that would leave me a block at the end to review all answers and then contingency in case of an emergency toilet break etc. My technique was to read the question in full, mark an answer on instinct and then confirm by reviewing each other answer in turn. I would flag questions I was not sure of the answer for. If I didn’t have an answer after my fixed time limit, I would flag and move on. Also, there were questions I immediately marked and progressed on from. This is a method of cognitive de-loading I used until I have warmed up and have the mental bandwidth to answer a complicated question.

Next, I would trawl to through flagged and unanswered questions. I would estimate the time per flagged questions from the time left and try and develop an answer. Following answering each question I would conduct a full review of all answers, repeating my rationale. For my contingency time at the end, I would be able to round on any particularly challenging questions. By this exam technique I could leave the examination satisfied that I had given my all.

Routine at peak – Christmas & New Year

Leisurely breakfast, cognitive awakening – newspaper reading/conversation.

1000-1100 session 1; 15 min break

1115-1215 session 2; 15 min break

1230-1330 session 3; 45 min break lunch

1415-1515 session 4; 15 min break

1530-1630 session 5; 15 min break

1645-1745 session 6; 1 hour break dinner

So essentially 6x 1-hour sessions across the day. If I had stuff to do morning/afternoon I would transfer some sessions to the evening. If I felt as though I was hitting a wall concentration wise or energy wise, I would take a longer rest, sometimes just walk away for the rest of the day.

Minimising degradation

As discussed earlier, I burnt myself out revising over Christmas and New Year. After 2 weeks of this routine, likely many of us I was irritated, not eating so well, hitting the coffee hard. When you really focus on something, it is easy for basic self-care to fall by the wayside. Christmas was a natural firebreak for me to switch off, after which I was back motivated. My advice is plan in fun activities. I limped to Christmas and then planned in for New Year in order to have things to look forward to – thereby motivating me. In my head I had build MSRA up to be an all-or-nothing event as it is the gatekeeper for CST. It need not be so ominous. Keep perspective, maintain quality of life activity and keep motivated. I recognise I am a fear motivated person more than anything else, and lost sight of the positives in life as I took myself into a revision cave for those 3 weeks. Remember we work to live not live to work! If the exam doesn’t go so well then take comfort in having given preparation your best and use that experience to come back stronger. Help each other and share best practice.

Conclusions

The first hurdle of CST applications drops many hopefuls from the running. Achieving a score that wins an interview is well within everyone’s grasp if they apply themselves to preparation in an efficient manner. We all have competing demands on our lives that may expend our time, energies and resources, but good preparation begins with first managing our lives. Secondly, we must understand the ask and our start point, to establish the work required. Thirdly we must plan in the required work, allowing for rest and fun activities, as well as contingency. Fourth, test yourself against the standard frequently and adjust preparations accordingly. Fifth, rest yourself in the days leading up to the exam. Arrive in plenty of time, with all the required documentation. Arrange parking. Ensure you are well-rested the night before, hydrated and well fed and prepared in case of headaches. Sixth, decompress when the exam is finished. Once the paper is in you can’t change the result. Celebrate having given your all as you see fit and be sure to take a nice break before your invitation to interview and beginning these preparations.

Getting into Core Surgical Training Part 2 – How to Prepare for the Interview

Resourcing

- Time: 20 hours

- Personnel: At least 2 others, current trainees, senior colleagues

- Equipment: Textbooks, medibuddy stem bank

- Course: RCSEd interview prep course

- Staging: ensure rested after MSRA. Low level interview prep 1-2 hours a week, advise ramp up to daily when notified of interview.

- Booking – Recommend a slot 1000-1100, a few days into interviewing period unless personal calendar requirements. Avoid post-prandial slump, end of day attention fade and start of day tech issues.

- Environment: tech compatibility checks, internet/cable upgrades/room setup i.e. lighting, background, angle of computer, choice of room, personal dress. Routine: sleep, hydrate, caffeine and alcohol management, shave if applicable, moisturise, hairstyle. Dress smart!

Guiding principles

Preparation

- Information gathering stage – HEE CST portfolio – ensure evidence letters are exactly as specified in most recent self-assessment scoring guide – there may be changes year to year but easy to have edited if close already.

- Ensure portfolio is optimally maxed out well ahead of time (secure the points) and maintain contact with signatories maintained in case updates required.

- Answer drafting – write and rewrite answers to the common questions. Try and variety of approaches, bullet pointing, chronological, narrative. See what works for you.

- Planning – time carve outs at work/home life, whilst tired and whilst fresh. Little and often with many others. Try out new things until you settle.

- Peer review – fellow applicants, current trainees, senior colleagues, cruel to be kind, multiple personalities. Self-record and get over self-judgement. Laugh if you mess up. Multiple opinions. Ensure Caldicott and data security principles always maintained.

Delivery

- Structures – time constraints mean important to present info and the “so what” concisely.

- ISPIESDRS – Issues, seek information, patient and team safety, intervention, escalation, summary, documentation, reflection, sharing.

- STARR – Situation, timing, actions, result, reflection

- SMAC – Sporting, management, academic, clinical

- Scaffolding rather than scripting – Advise against full scripting. Soundbites within a natural conversational style is best.

- Delivery & narrative fluency – once very familiar with subject matter and your manners of presenting the fluency will come through.

- Tone, emphasis, humour, stand out – but this is a professional interview.

- Body language – upright, eye contact with camera, gesticulation and hands, smile!

- Practice being thrown off or losing track – hostile interviewer vs docile interviewer providing nil direction.

- Smile and say hello at the start of your stations. Thank the interviewers for their time at the end. Positivity radiates. The timings are not that tight. Time for some good old fashioned British manners.

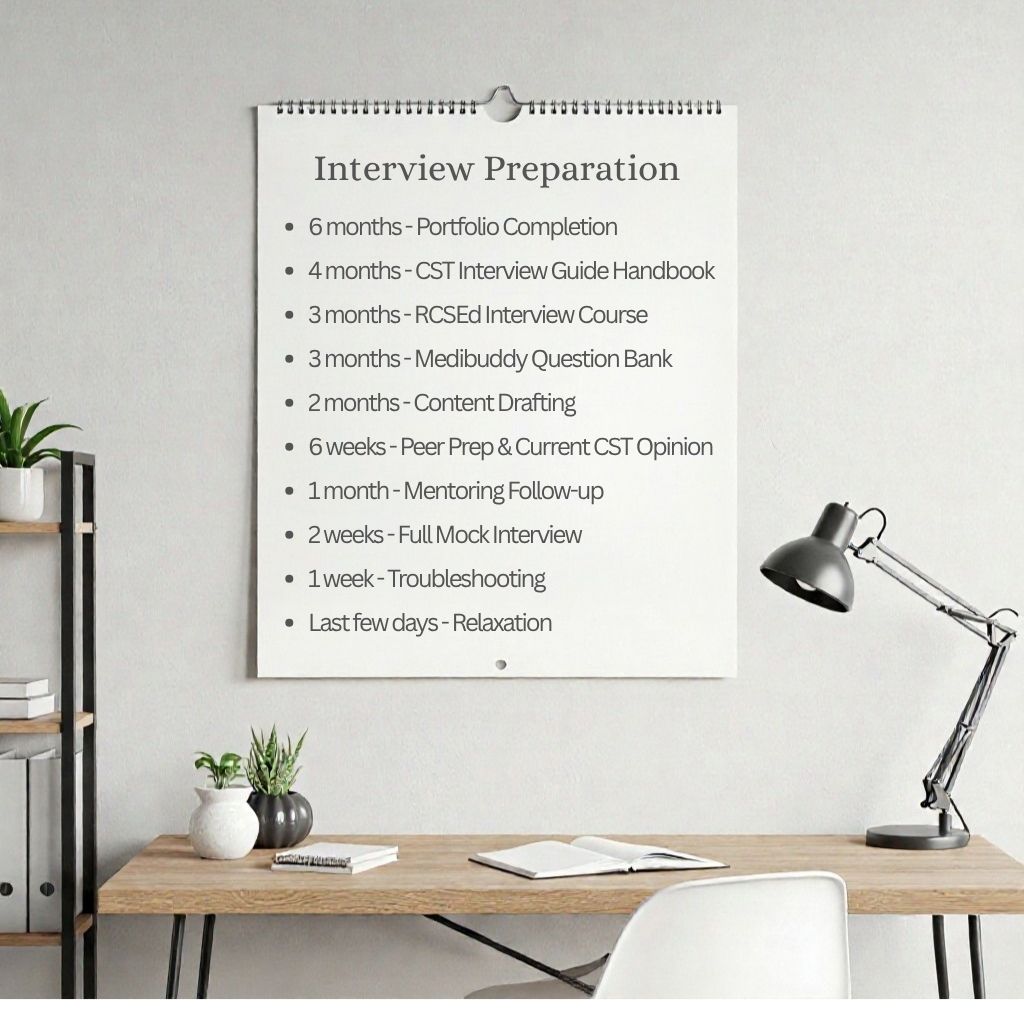

Timeline

-6 months have all portfolio components complete, and letters written as per HEE webpage requirements – be prepared to amend.

-4 months – CST interview guide handbook

-3 months – RCSEd interview course

-3 months – Medibuddy interview question bank

-2 months – content drafting

-6 weeks – fellow applicant prep and current CST opinion – informal, phone call or VTC.

-1 month – RCSed interview course mentoring follow-up

-2 weeks – full length mock interview with rough scoring

-1 week – troubleshooting

-last few days – relaxation

Interview format

The interview now consists of 2 stations – Portfolio, and Management and Clinical, equally weighted at 45% of overall score each, to make a total 90% of your overall CST score. The remainder 10% is from your MSRA score.

- Portfolio station – 15 minutes (45% of your rank)

- 1 pre-prepared 3 minute presentaion

- 2 minutes of questioning on the presentation

- 2 x portfolio questions – 5 minutes each on two of the portfolio domains. The assessors will decide which two will be discussed, and this will vary from candidate to candidate

- Management and Clinical Station – 15 minutes (45% of your rank)

- 1 management scenario question

- 2 x clinical scenario questions

- 5 minutes allowed to answer each question. Assessors may ask follow ups to explore your clinical reasoning and knowledge of management

The portfolio station examines objective skills across 4 domains, including commitment to specialty, involvement in the full spectrum of quality improvement, presentations and teaching. These are the only “guaranteed points” you can earn ahead of time. The interviewers then choose 2 of the domains to ask follow-up questions on.

Ensure your portfolio is prepared early according to the evidence requirements circulated in the most recent year.

Less is more regarding evidence letters. Make it easy for the evidence verifiers/panel to understand what you have done, when and in what manner and who is vouching for your work.

You will have to self-appraise your work. Ensure you appraise rigidly in-line with the guidance. If you overscore and misrepresent your work this can be seen as a probity issue and result in a score of 0. If you underscore yourself the interviewers will not mark you up. Be judicious and be prepared to defend your self-appraisal as a mature learner.

The clinical station provides 2x 5 minute clinical scenarios which will draw upon your clinical approach, decision making and communication skills. The clinical level of such scenarios is set as a doctor who has completed Foundation Year 2.

The management station asks you to deliver a presentation on an aspect of character and take follow-up questions over 5 minutes. Then follows a management situation in which you will be asked to appraise and manage a workplace dilemma.

We’ll break down each station below.

Station 1 – Portfolio

- Domain 1 – Commitment to specialty

Portfolio

The first evidence required is the summary page of your surgical logbook, with points awarded based on the number of procedures listed. 40 operative cases scores you maximum points and is absolutely achievable inside of a few taster weeks. Try to achieve a mix of elective and trauma cases to reflect the breadth of specialty work. You can also include emergency department minor procedures. I would advise using e-logbook.org – it allows you to generate a handy summary sheet to tabulate your cases.

It is critical that the logbook is verified by a consultant with a signature, date, GMC number and appointment on each page. You should be judicious with how you list procedures to ensure the record is accurate and legitimate. A current controversy amongst surgical trainees is over the correct recording of procedures in logbooks – be sure to understand the meaning of each classification. Some classifications are clear cut for example performed, whilst others are open to abuse such as Supervised Trainer Scrubbed versus Assisted. Be prepared to defend however you have listed a procedure in the interview. Whilst there will be experienced applicants for CST, you will not have Performed a Whipple’s Procedure!

The interviewers may choose to ask follow up questions on this domain. These will largely be based around justifying and clarifying your involvement in the procedure. Additionally interviewers may look to examine your understanding of the importance of logbook through surgical training and beyond. Be sure to read up on Intercollegiate Surgical Curriculum Programme (ISCP) and ARCP requirements.

Letter confirming surgical taster week

Maximum points are scored for conducting 5 days of taster time in a surgical specialty, evidence by a formal letter stating the 5Ws, what, where, when, who supervised and what learning experiences were gained. As with all evidence letters, ensure the supervising consultant’s signature, date, name, GMC number and appointment are present. Whilst during COVID surgical placements in foundation training gained points, they are now not considered for scoring.

Follow-up questions around taster weeks will look to understand your learning experiences and discuss future career aspirations to demonstrate your commitment to surgery.

Domain 1’s portfolio and taster week are easy wins and usually obtained at the same time. Everyone will have maxed out points in these categories, so ensure you do too.

Domain 2 – Quality Improvement / Clinical Audit

The quality improvement field is a broad spectrum spanning single cycle audits to 2nd loop quality improvement initiatives. For more developed projects you score more points as per the table below.

For top marks you will need a letter confirming leading a Surgically themed QIP that has demonstrated changes and involvement in all stages. Again, ensure this has the supervising consultant’s signature, date, name, GMC number and appointment.

A second letter is required to demonstrate presenting your work. Crucially this does not have to be a national level meeting. Any learning meeting will be sufficient. Present early to ensure you’re not scrambling for somewhere to present. Practice meetings, foundation training meetings and departmental QIP meetings are ideal. If you do a complex project, ensure you bank a presentation of the first loop, just in case the project doesn’t complete etc.

Surgically themed need not mean secondary care – you could use a medical or primary care aspect of the surgical care pathway. Be creative, keep the project achievable and accessible.

Ensure the organiser of the meeting prepares a clear letter stating the QIP/audit name, meeting name, dates and times, and of course their personal identifiers, to include name, GMC number, appointment and signature, as per the HEE evidence guidance.

Follow-on questions around QIP/Audit are likely to centre on justifying your involvement in each stage, appraising any lessons learned and how these are applied to sustain change. The interviewers may ask what your future aspirations are within QI and the role of this in surgical training. You may be asked to define project types within Quality Improvement spectrum including audit, QIP, service evaluation and research – so be prepared to rattle these definitions off and explain their importance.

Domain 3 – Presentation prizes and publications

This is perhaps one of the more time intensive sections to get done. The assessed activity is presenting information to the academic world, whether this be in written or verbal form. The subject matter that you are presenting is a whole other kettle of fish.

Whilst prizes and publications appear to be equally weighted, publications are more likely to stir interest amongst the interviewers. Local prizes may not stand up to scrutiny. It is a safe bet to not use the same evidence across multiple domains – although refer closely to the guidance on submitting portfolio evidence, this may be permissible.

For publications be prepared to justify your level of involvement. The contributorship statement is vital to explain this. Whilst first authorship is the high scoring element for this domain, if you are simply a front for writing the paper with no involvement in the planning and execution of the research then your first authorship may not stand up to scrutiny.

Another requirement is to include the PubMed ID on the paper. You don’t have to have published in the New England Journal of Medicine for the paper to count – so long as there is a PubMed ID it counts! Upload the paper showing PubMed ID – that is all the evidence you need.

In terms of what research you conduct, I would strive to get a basic science quantitative project. Whilst perhaps less accessible to doctors of our seniority, it will garner more interest and be more novel that the easier to conduct qualitative opinion based projects that some resident doctors choose.

Likely follow-on questions will centre around your involvement in the research project, what you learned from it and what you plan to do with the information gained. Interviewers could also take a governance angle on the paper and evaluate your understanding of how research is planned, conducted and processed within a research strategy – and also why it is so important. Understand the key ethical approval pathways and codes of practice in research. Always be aware of the literature surrounding your research and have plans to build upon your project in the future.

I was able to link together multiple research papers on novel topics in order to demonstrate a personal direction of travel in research. I had presented the research to many different organisations and won a national prize and thus was well versed to answer any common questions arising.

Domain 4 – Teaching

Teaching is one of the more time intensive sections due to the requirement to engage with local educators and devise a curriculum in line with students’ educational requirements, and then arrange attendance and facilities with medical school/hospital education department. This will be easiest to achieve over a period of a few months with weekly sessions for medical students for example. However, a crash course on teaching skills / Train the Trainer course would still qualify you for indicator D if you left things late – this can be done in a day.

I would recommend having a single point of contact within a medical education department who can provide curriculum information, scheduling, collate feedback independently and assist with seminar room availability. The confirmation letter for the portfolio should come from a supervising Consultant in order to assure the veracity of the teaching delivered.

A second letter should detail that feedback was reviewed as satisfactory by supervisor. If any improvement proposed, ensure you have evidence of reflection and implementation. I would use a Likert-style MS forms to collate and have this accessible from session 1, so that you can be reactive as a teacher. Anonymous feedback and data handling have to be appropriate – advise medical education centre administrator to handle the feedback collection – they often have a system for feedback and certification anyway.

Follow on questions might include explaining the stages of identifying learning needs and delivering the sessions. Include practical aspects to arranging sessions alongside the conceptual aspects of how to teach. If you have any formal qualifications in medical education then be sure to bring them up. I conducted a Postgraduate Certificate in Medical Education and a Train the Trainer Course and this gave me a number of talking points around teaching.

Training governance is vital and indeed you may be asked about this during your follow on questions. This may include explaining information gathering, presentation, assessment and peer review of teaching.

You may also receive more nebulous questions on the importance of medical education and our role in it through all stages of specialty training. We must be both the learner and the teacher. A mark of a successful core surgical trainee is the ability to learn with varying trainers and support varying juniors.

Station 2 – Management and Clinical

Management Scenarios: approach – ISPIESDRS

Management scenarios can be complicated, with many competing priorities that each need addressing in turn. The commonly used framework is SPIES, but I advocate the use of an expanded acronym called ISPIESDRS. See below for a summary.

- I- Issues – Bullet point key issues, drop buzzwords

- S- Seek information – Cross-reference with others without gossiping!

- P- Patient and team safety – Is there an immediate threat? Delayed threat?

- I – Intervention – Urgent or routine? Is this at my level? Who can I get to intervene?

- E – Escalation – Who needs to know? Clinical vs managerial vs candour to patient. Colleagues to prevent repeats, n.b. avoid gossip.

- S – Summary – Recap issues and how they have been addressed.

- D – Documentation – Patient notes, emails, security statements

- R – Reflection – Mention Gibbs model for example

- S – Sharing – Reflection groups, peer training, ES discussions

I signpost going through each phase by stating and emphasising the title, with breaks to emphasis transitioning between phases. I use phrases such as “the key issues here are x,y,z the most significant being,” and “my intervention is” and “I would escalate this to.” It is important to address each stage in order of significance, whether that be due to severity of implications or timing of implications. The phases of ISPIESDR should flow naturally into each other, the previous always providing ammunition for the next phase.

Issues

It is vital to outline the key issues in the scenario, but try and keep this to three or less. Think headline style summaries.

Seek information

Specify how you would gather information, whilst maintaining dignity for all involved. You have to be sensitive as confidence can be undermined and team unity affected by aggressive information gathering. You are seeking information in order to secure clinical safety and quality which should be the desire of the full team. Avoid gossip and engage sensitively with individuals if appropriate. Sometimes you may have to offload information gathering to other individuals such as HR or a departmental lead.

Patient safety

Whether patient safety is affected in the past, present or future we have a duty of candour to our patients in order to maintain their confidence. You may need to intervene immediately to prevent harm, in order cases you may be able to seek advice prior to intervening or have someone else intervene. I would also consider patient perceptions of safety here. Communication with patients is essential to ensure their ideas, concerns and expectations are address and that they do not feel left in the dark.

I would also consider colleague safety here, both physical and psychological. We may need to intervene against the patient rather than for them. Hence it is important to appraise the threat they may face. Other patients on the ward and visitors are also potentially in the firing line. As someone who has been on the receiving end of violence from patients this is strongly ingrained in me.

Intervention

You may need to make a small immediate intervention. For anything significant you should seek support of a more senior professional who is appropriately trained and experience. We may need to intervene via non-medical teams such as HR, security or departmental staff.

Escalation

It’s essential to escalate all issues to another individual in order to second check your thoughts and actions. As trainees we have our daily clinical supervision chain and educational supervisor who will be happy to discuss any management dilemmas as part of your training. They will known better how to handle things and ensure that safety and quality are maintained.

Escalation could also include discussing with your indemnity provider, or even moral support for you from freedom to speak up teams, doctors support lines and pastoral care.

Summary, documentation, reflection, sharing

The S DRS section nicely wraps up the scenario by stating the key issues and how they have been addressed, ensuring that actions are recorded appropriately and that we engage with others appropriately to share lessons learned. There are appropriate fora in which to discuss such issues on a regular basis.

Scenario subsets

Patient safety

Perhaps the most common question subset to be asked. These scenarios draw upon your clinical understanding and see how you apply your knowledge practically in ethically challenging scenarios. Some scenarios will be set following on from harm occurring, some with near misses, others with future harm potential. It is down to you to appraise the risk posed and understand the appropriate follow-on actions.

Team dynamics

The second most common question subset to be asked. Surgical teams are always a mishmash of personalities, some of which are harder to gel with than others. Such management scenarios want to examine your approach towards working with difficulty individuals and how you are still able to ensure safety and quality of care. Of course, maintaining psychological and even physical safety are also vital.

Supervision up, down and laterally

A key distinction between foundation training and core surgical training is our responsibilities to supervise others and have a greater level of trust placed in us by our seniors. It is vital we understand the supervision relationships present and set appropriate boundaries to secure patient safety.

Personal probity

Typically scenarios will be you looking in at someone else’s probity being thrown into jeopardy rather than your own being questioned. The emphasis here is thrown onto seeking information and how the potential probity issue is assessed and intervened against. Early escalation to appropriate agencies alongside intervention to protect patient and individual safety are emphasised in such scenarios.

Follow-on questions

Follow on questions will naturally look to examine the characteristics required of a good core surgical trainee. I found it helpful to try and visualise the common professional dilemmas that I had encountered previously and that I would be likely to encounter in Core Surgical Training. I would think through the key issues and stakeholders and come up with an approach to each situation. This helped me to think on my feet when the unforeseen professional dilemma questions come out.

Clinical

Fresh Cases in Hospital – Trauma vs Critical Illness

You will have 2x 5-minute clinical scenarios, of which usually 1 is trauma focused and the other is atraumatic. The situation is read out and you will be invited to describe your approach to the scenarios, followed by a couple of follow-on questions.

We can break down the potential scenarios into a few groups: Trauma vs atraumatic, and then pre-op vs post-op. For trauma you should be familiar with ATLS principles, and for atraumatic (or critical illness) you should be familiar with CCRISP guidelines. These provide a robust structure for your clinical approach and will stratify your management of the case. Essentially, they are A-E assessments with pertinent interventions and information gathering included. You need to be able to rattle off the assessments in full with confidence, whilst still stressing the most pertinent points.

Nonetheless, often underappreciated is scene-setting (described below.) The examiner will want to know that you understand your role, where you are seeing the patient, who else needs to be involved and how you will handle the patient (and maybe their relatives.)

Consider scene setting elements:

- “I will immediately attend to the patient, so long as there are no more pressing clinical commitments” i.e. if in surgery already.

- Consider where you are, what you have to hand – i.e. crash trolley, ward team, bedside data (vitals), duty team.

- “I would see the patient in a resuscitation area”.

- “I would ensure senior colleagues, including an intubator were present in the resuscitation area, introductions were made, and roles established. I would ensure to receive the pre-alert brief and prepare for my duties”.

- “If multiple casualties were arriving, I would ensure that a Major Incident had been declared”.

- “I would ensure the major haemorrhage protocol had been activated and that trauma blood packs were on the way”.

- “I would be sure to introduce myself to the paramedics/pre-hospital team and take their handover, ensuring I clarified pertinent points”.

- “I would introduce myself to the patient, seek their consent to provide care to them and explain what we were doing throughout.”

- “There may be family members with the patient who may require compassionate handling – this will be an emotive time for them. They may be invited to leave the treatment area or may be invited to stay in the room if they wish. Certainly, they will need to be considered for updates, so long as the patient consents and this does not impair the delivery of clinical care”

A-E approach

Be systematic and follow the appropriate principles of ATLS or CCRISP, employing protocols such as Sepsis Six, Massive Haemorrhage and Anaphylaxis/ALS as relevant. Be thorough in assessing, using all the tools reasonably available without wasting time. It is important to state priority orders and specify the timing of and reasoning behind interventions. If you are going to escalate at any stage, talk through the reasoning and the practicalities of doing so.

Quite underappreciated is the delivery of your answer. There is so much information that will come out of any A-E protocolised approach over the several minute soliloquy. Ensure that you do not rush and instead pace your answers. With practice aim to have rehearsd

Post A-E assessment you should step back and identify the pertinent parts of the information gathered – verbalise this “I will now step back and consider all the information I have gathered”. Then list key concerns – “My key concerns are 1. 2. 3.” Emphasis your priorities and next steps – “Priority 1 will be x, to be delivered by staff member y; priority 2 will be z, to be delivered by myself”.

Always have both the most likely differential in your head, but also enunciate the most dangerous differential. Consider investigation and interventions in clinically appropriate order, but have in mind the practicalities of each. For example bedside tests versus specialist imaging that will reasonably require discussion with the on-call radiologist as well as their interpretation.

Work up in terms of invasiveness. It is important to corroborate information from enough sources until you have a clear understanding of the situation. But be judicious in your investigations! The patient does not need an Everything-ogram! This will delay their time to treatment, whether it be surgery or conservative management.

Although the clinical scenarios are framed to test your clinical acumen, remember that communication and working with others are vital in surgery. Consider what support you may need as well as what support is available. This can be requesting support from seniors, laterally with colleagues or down to juniors that you may need to delegate roles to. You may need acute support or maybe delayed. Of course, you will get a measure for this depending on the specific situation faced.

It is not just colleagues you need to communicate well with. Consider how you will communicate with the patient to ensure person centred care. Also consider how you may interact with accompanying relatives, friends and colleagues. Drop key buzzwords here including sensitive discussions, compassionate dialogue and of course ensure appropriate consent for any care. You may allay concerns and reassure others. Ensure you are aware whether the patient has consented to information sharing, and if so ensure their dignity is maintained and there is appropriate information sharing.

Scene management also includes the time following involvement in the case. You should be clear that you would document clearly when able, conduct discussions or referrals in clinical priority order and record these contemporaneously. It is important that the full team providing care are appropriately briefed to ensure shared understanding and appropriate contribution to the management plan.

For the trauma team consider debriefing the situation to set the narrative straight for everyone – they may have been drawn into their own tasks. There may be things that people want to discuss – to compliment great performance, offer constructive feedback, or even receive peer support.

Finally, an underappreciate area is closing down the scenario. You will want to summarise your findings, next steps, subsequent steps, communication to the patient and relatives, handover the patient and consider yourself how you will reflect on and learn from the patient. This conclusion should be pithy to cap off your answer.

Remember, not all roads lead to surgery! We must consider the patient’s clinical trajectory, our own knowledge, skills and experiences and the implications of anything we choose to do. Palliative and conservative care is absolutely an aspect of surgical care, so give it due weighting.

The follow-on questions may have been answered already by your approach. Sometimes the examiner may stop your approach delivery, sometimes they may let you keep going. In any case, when the questions come give a clipped answer. You may get a closed question. If you do not know the answer a safe bet is always “I am not sure. I would consult a senior colleague or reputable textbook.” You may get a somewhat open question. Try not to waffle.

Post-operative scenarios

As an aside from fresh cases, your clinical scenario may be less acute and based around a reassessment of an already managed patient. It is important to still conduct a thorough A-E assessment and not be drawn by information that may be a red herring distracting factor.

My advice is to break down the ground around post-operative patients including what has been the post-operative course and when did the problems develop.

In those just returned from theatre you are mostly looking at Airway and Breathing issued related to sedation and ventilation. In Circulation you are looking at blood loss. For Disability key concerns to address are pain management, GCS, delirium and hypoglycaemia. In Extremities key concerns are around packaging, thermal comfort, timing of eating, drinking again, bowel and urinary opening and environmental factors such as family visiting.

A few days in we may be developing nosocomial infections, as well as potential anastomotic leaks. Thombi are also another relevant concern as is bleeding due to blood thinners.

Other things to think about include falls and confusion, discharge planning and ongoing care requirements. The surgery may have changed their life by debilitating them or by restoring function. We must consider how we continue to cement the gains from surgery or mitigate the negative side effects. Operative and rehabilitation failure should be minimised given the formulisation of much care nowadays. Nonetheless we must ensure the patient’s continued buy in to recovery.

In trauma post-op cases, of course consider whether a secondary survey is required, or the primary surgery may just have been damage control surgery or staged operation.

For inpatients always consider whether the post-operative complication be managed conservatively as well as whether it may necessitate a return to surgery. It is our duty to ensure that patients are always optimised, regardless of whether they are likely to return to surgery. Ensure a valid group and save, ensure hydration and appropriate feeding.

If you recognise a potential need to return to theatre then ensure you escalate in order that a more experienced surgeon can provide direction. Your role becomes more so to optimise the patient for surgery and communicate with relevant parties. The patient should be NBM, with recent blood results including group and save confirmed. Plans should be discussed with anaesthetist, theatre manager, surgeon, ward/ED team and of course the patient! If the patient requires consenting, ensure this is done appropriately, insofar as someone who is qualified to perform the procedure and understands the risks and benefits is giving clear information to the patient.

Follow on questions

Your approach may have provoked specific questions. The interviewer will look to confirm understanding or clarify earlier points. They may wish to delve into your understanding of what happens next regarding surgery or even the non-surgical aspects of patient care.

- “And if the patient is taken to surgery to perform x operation, what will be your key parts of post-operative management”

- “Which procedures might be considered?”

- “How might you clinically supervise your juniors in this situation?”

- “Which aspects of the patient’s history would make you most concerned pre-theatre and how do you optimise them for the anaesthetist?”

Conclusion

This article provides a combined approach to preparing for your CST interview. Whilst much of the portfolio substance and professional experiences will have been built up over your earlier career, this is likely the first formal interview you will have faced for many years. Engage early with preparations, have a plan, identify and attack weak areas, seek support and practice practice practice!

Best wishes with getting into surgical training!